Moalboal’s Sardine Run: A Swirling Spectacle

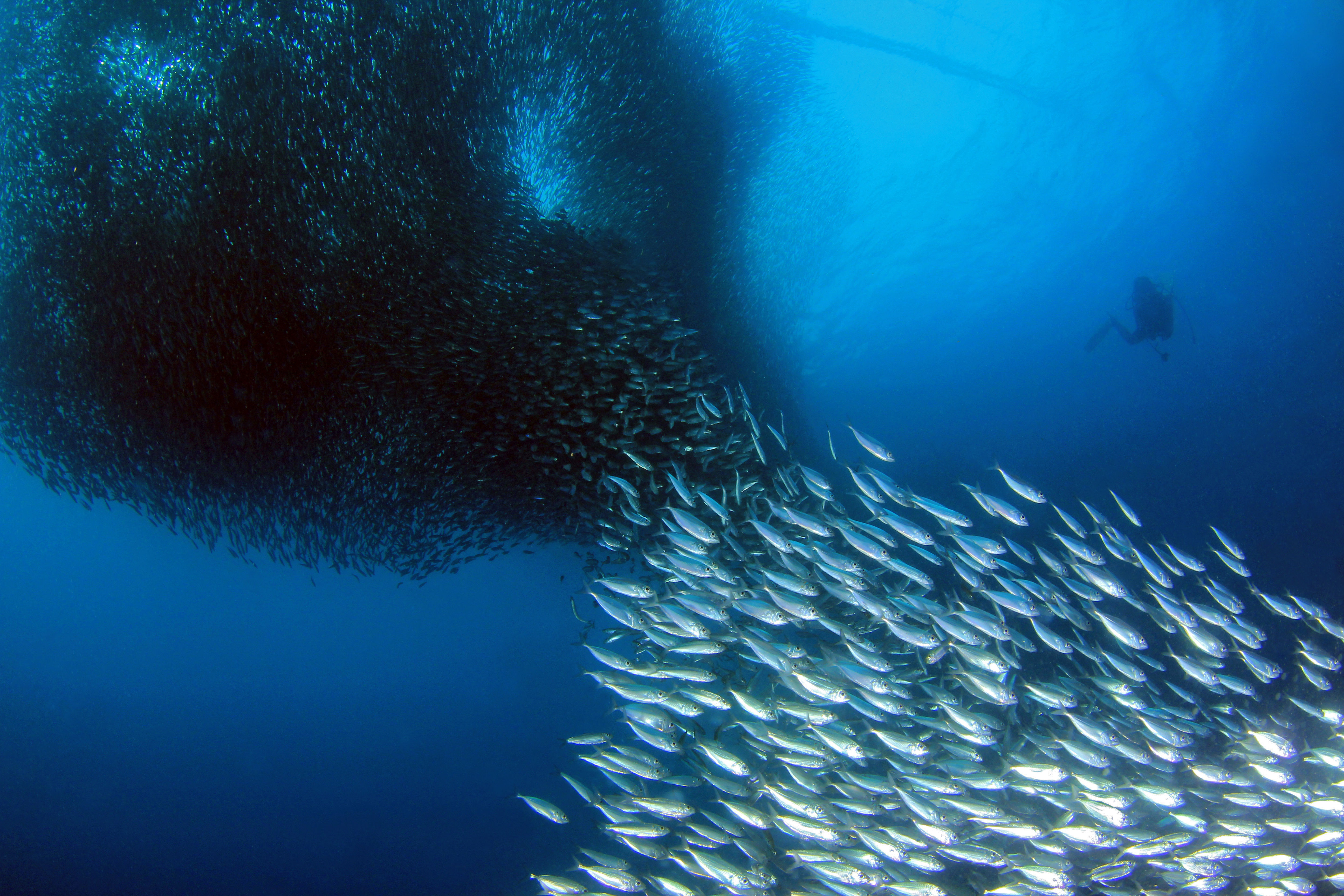

It starts with a flicker. Then a shimmer. A silver flash that grows into a wave, a vortex, a living tornado. Off the shores of Moalboal, a laid-back coastal town in the Philippines, millions of sardines move as one—an endless ribbon of muscle and instinct that ebbs and flows with every ripple in the current. To dive into this sardine run is to enter a hypnotic world of motion and light, where fish pulse through sunbeams in perfect unison and predators wait in the wings to strike.

This isn’t a rare seasonal phenomenon—it happens year-round. Just a few fin-kicks from shore, scuba divers and snorkelers can plunge into one of nature’s most accessible marine spectacles. And unlike many marine encounters that require remote travel or deep walls, Moalboal’s sardine run unfolds right in front of beachside cafés and dive shops, beneath the palms and pastel sunsets of Cebu’s southwestern coast.

For those seeking both high drama and high accessibility, the sardine run of Moalboal offers a front-row seat to one of the ocean’s most remarkable shows.

The Science Behind the Swirl

Unlike the famed sardine migrations in South Africa, the sardine run in Moalboal isn’t driven by seasonal shifts. Instead, it’s a year-round congregation of Sardinella species that thrive in the nutrient-rich waters just off Panagsama Beach. Cool upwellings from the Tañon Strait bring plankton blooms close to shore, creating a buffet that keeps these baitfish tightly clustered in massive schools, often no more than 20 meters from land.

This abundance of sardines doesn’t go unnoticed by predators. Giant trevallies, jacks, tuna, and even thresher sharks occasionally cut through the shimmering mass in lightning-fast strikes. Watching them hunt is like watching brushstrokes on water—fluid, sudden, and stunning. For divers, it’s a rare opportunity to witness the full circle of marine life unfold in real time, in clear, shallow water.

Ecology and Conservation

Moalboal’s sardine run is not just a tourist attraction—it’s a critical ecological event. Sardines serve as a foundational food source for countless species, and their presence supports the health of the reef’s entire food chain. The reefs themselves, however, are under pressure from coastal development, fishing, and the growing popularity of marine tourism.

Fortunately, the local community has taken steps to preserve the area. Marine sanctuaries near Pescador Island and the Panagsama reef zone help reduce overfishing and provide refuge for juvenile fish and coral restoration. Still, diver behavior plays a key role. Avoiding contact with the school, maintaining proper buoyancy, and respecting marine life all contribute to the long-term sustainability of this phenomenal experience.

Top Dive Spots for the Sardine Run

Panagsama Beach (House Reef)

This is the beating heart of the sardine run. From a simple shore entry, divers and snorkelers are immediately surrounded by towering baitballs that stretch tens of meters across. The density of sardines here is staggering, and they can be seen both shallow (5–10m) and deeper down the reef slope. Because the school is semi-resident, this site delivers daily spectacle with minimal effort.

Pescador Island

Just a short boat ride from shore, Pescador Island is one of Moalboal’s crown jewels. Steep drop-offs, coral gardens, and large schools of fusiliers make this a favorite among photographers. Sardine sightings are occasional here, but the dramatic walls, hunting jacks, and coral diversity make it a worthy companion site to the house reef.

Talisay Wall

North of Panagsama, the Talisay Wall offers colorful coral structures and the occasional drift of sardines along the slope. It's also a hotspot for turtles and macro life, making it a versatile site for those hoping to combine wide-angle sardine shots with some small critter hunting between dives.

Kasai Wall

With its gentle slope and excellent visibility, Kasai Wall offers a more relaxed dive, often ideal for beginners or macro enthusiasts. Sardines occasionally swirl through, especially when currents shift, and you might catch glimpses of them against the vibrant coral background. Soft corals and anemones also attract clownfish, shrimp, and nudibranchs, offering photo opportunities between sardine sightings.

Airplane Wreck

This small twin-engine aircraft, intentionally sunk for divers, lies at a depth of around 22 meters and makes a unique backdrop for sardine photography. While not always surrounded by baitballs, sardines sometimes drift into the area, offering a surreal contrast between natural movement and man-made relics. It’s a great site for photographers seeking something different.

Best Practices for Divers and Underwater Photographers

It’s easy to get excited in the presence of such overwhelming beauty, but the key to a memorable sardine dive lies in restraint and respect. Sudden movements or aggressive chasing can scatter the school, ruining the moment for everyone—and stressing the fish unnecessarily. Instead, approach slowly and hover at the edge of the baitball. Let the sardines envelop you.

For photographers, wide-angle or fisheye lenses are essential to capture the full drama of the swirling mass. Shoot with natural light when possible—early mornings and late afternoons offer golden light rays that pierce the water and illuminate the school in breathtaking ways. If using strobes, diffuse your light to avoid harsh reflections off the silvery scales. And always be mindful of other divers and marine life when framing your shots—patience yields the best images.

More Than Just a Dive

Diving the Moalboal sardine run is more than a thrill—it’s a reminder of the ocean’s raw, rhythmic power. To be inside that vortex of life is to feel the pulse of the reef itself, ancient and enduring. But it is also fragile. As climate change, overfishing, and tourism take their toll, places like this need not just admiration but protection.

When we choose to witness without disturbing, to document without exploiting, we become not just visitors—but stewards. The sardine run will continue, indifferent to our presence, but we have a responsibility to ensure it persists for those who come after us. In that dance of silver light, we glimpse not only nature’s choreography—but our role within it.